by Casey

When I first started my journey along the Buddhist Path, I was intimidated by monastics. They looked too grand and holy silently lined up in their orange robes on the early morning streets of Vientiane, Laos, where I live and work, or solemnly chanting unintelligible Pali blessings while sitting stone-faced at funeral ceremonies. I dared to get close enough only to drop a handful of sticky rice into their alms bowls, but not to make eye contact, much less start up a conversation about the Dhamma. I steered clear of these bald-headed figures as best as I could even after I started going to monasteries to practice and serve, afraid that I would say or do something improper, or otherwise disrespect them by accident. I rationalized that there was no need for me to associate with monastics anyway. I had my books of suttas and my daily meditation practice. Besides, in this modern day and age I could just pull up a talk by Ajahn Brahm on YouTube and watch from a safe distance. Surely I could do without direct interaction with monastics so long as I had the word of the Buddha and the internet.

Yet as anyone who has been fortunate enough to spend time around fellow practitioners has probably already discovered, there are a lot more layers to the Dhamma that come out when it is a living, breathing essence flowing through the lifeblood of a community of monastics and laypeople that is far more vibrant and nuanced than when it is exclusively absorbed from the pages of a book. If I had not started to figure this out for myself, I probably never would have ended up here at the Anukampa Vihara for the tail end of Ajahn Brahmali’s recent UK teaching tour in the first place. And if I had not realized the beauty of this treasured living Dhamma ahead of time, I certainly would have felt it when I arrived at the vihara in Oxford, at which time I was immediately swept up into the flood of peace, generosity, and metta that this community of Dhamma friends had been building up long before my arrival in the UK. The people I met who had joined Ajahn Brahmali’s retreat emanated auras of gentleness and tranquility, greeting me with the bright eyes and warm smiles of those who have been able to touch something deeper and kinder in themselves than any of us are typically able to reach on our own in our usual busy lives.

As I travelled with Ajahn Brahmali and the Anukampa community during the last week of talks, I experienced the same kinds of feelings for myself. From the first talk I attended at the Oxford Buddha Vihara to the day retreat hosted by London Insight Meditation at the Jamyang Buddhist Centre, and even back to the small community at the Anukampa Vihara itself, I found myself constantly surrounded by other people sincerely striving to reduce their own suffering and that of all other beings through thoughts, speech, and actions steeped in what is wholesome–moral sila, peaceful samadhi, and sharp wisdom.

It seemed that each new space I stepped into was awash in good intentions and the positive energy of all the people who inhabited them, allowing me to share in the peace, joy, and energy of a community that had come together to rejoice in the teachings of the very monastics who had once so intimidated me. The monastics were the core of the community, and the community pulled me to the very doorstep of the Dhamma. After years of practice during which I had mostly sat striving alone, holding onto some distant awareness of the breath through a raging sea of agitated thoughts, this community of practitioners proved to me what teachers like Ajahn Brahm, Ajahn Brahmali, and Venerable Canda had been saying all along. The practice is not an act of willpower, but a natural unfolding of mind that occurs when we incline ourselves in the right direction. Surrounded by so many people well-inclined towards kindness and letting go, my mind naturally followed suit. I finally felt like I was getting a taste of the true flavour of the Dhamma–not the spicy burn of forced effort, but the soft, sweet flavour of the natural underlying joy that all of us find when we put everything down and make space for it. It is one thing to read about such a thing and another thing entirely to be immersed in it at the centre of a crowd of spiritual friends, laypeople and monastics alike.

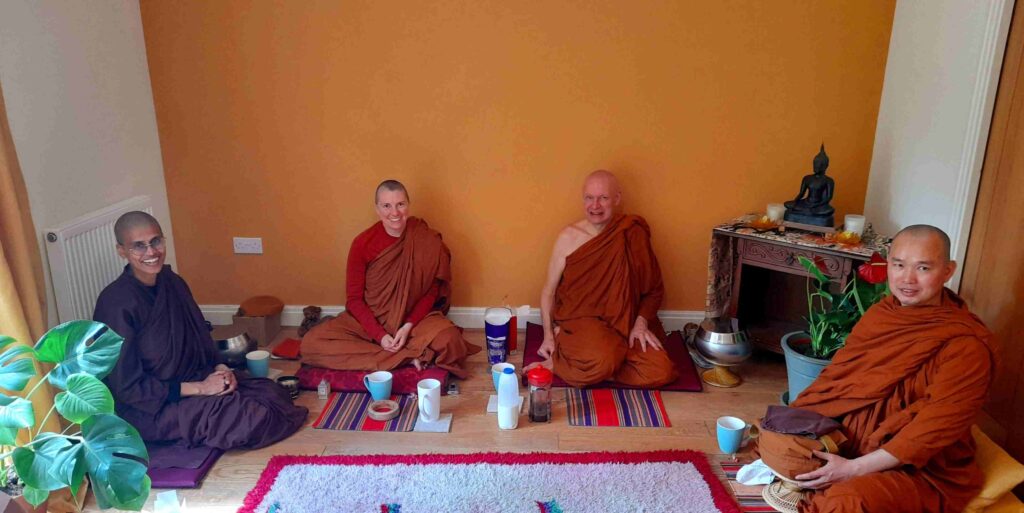

To watch the monastic life lived sincerely is to see echoes of the Buddha himself. It is true that many things have changed since the Buddha’s time. Now instead of walking barefooted down dusty paths, our retinue of monastics and lay supporters waited on a platform for our delayed train to Bristol, checking for updates on our smartphones while Ajahn Brahmali sat on a bench translating Pali texts on his laptop. Yet the heart of the monastic lifestyle remains the same. To travel and share the Dhamma lies at the core of monasticism, and for me, being able to witness this process in action was a priceless gift. Just as the Buddha and his supporters did more than 2500 years ago, still we were traveling from town to town, wherever there were people willing to lend an ear to the profound Dhamma and practice with good will and sincerity. I could tell that in spite of the whistles and bells of modern communication and transportation that I was witnessing Buddhism in its truest, oldest sense. It is thanks to the compassion and hard work of monastics like Ajahn Brahmali, Venerable Canda, and Venerable Upekkha that even after thousands of years, we still have the opportunity to witness this noble way of life in person to this day.

After a week of Dhamma talks, traveling, dana meals given and received, and quiet tea time with the monastics, I got to see not only the Dhamma as a logically sound philosophy or even as a strictly causal path that ultimately leads to cessation, but as something that was very much present and very much alive. Just as all living things, I also saw how the Dhamma was growing wider and deeper, putting its roots down in new territory. It is an amazing and wonderful thing to see the strong foothold this practice holds here in the UK, on a piece of land so far in time and geography from the land where the Buddha first taught, but where his teachings are just as valid and precious as ever. It was a special treasure for me to witness a room full of people discussing the integral importance of the bhikkhuni ordination as part of this tradition, a simultaneous return to the roots the Buddha himself laid down for women practitioners as well as an integral part of the new growth that is possible in the practice and in the community when all people have the opportunity to undertake the practice in its full scope.

At his last talk, Ajahn Brahmali voiced his wish that the audience might see the monastics as cute and cuddly (cuddly from a distance, he specified). It was an image of monastics that would have been almost impossible for me to even a year or two ago, and yet, I can say that during my past week with the dual Sangha of bhikkhus and bhikkhunis, I have finally felt that (distant) cuddliness. The warmth, metta, and goodwill I experienced in the presence of beings so dedicated to the Path the Buddha laid out was undeniable. Indeed, this is another echo of the Buddha, reminding me that while monastics may look intimidating, through them one can find a reflection of the true compassion of the Buddha, passed down through the Dhamma and Sangha to reach us in a very close and personal way even to this day. To show us the way to this compassionate path and help the Dhamma come alive to each of us is the gift that the Sangha gives. This is why the Triple Gem is necessarily triple and not double. By looking into the gem of the Sangha, we can see the reflection of the Buddha looking back at us through the generations of his students, the bhikkhunis and bhikkhus who continue to offer us teachings to this day. It is here in this gem that we can get a glimpse of the very compassion that motivated the Buddha himself to teach the Dhamma that continues to bring us all together, leading us closer to each other, closer to ourselves, and closer to the Truths that the Buddha unearthed.

by Casey