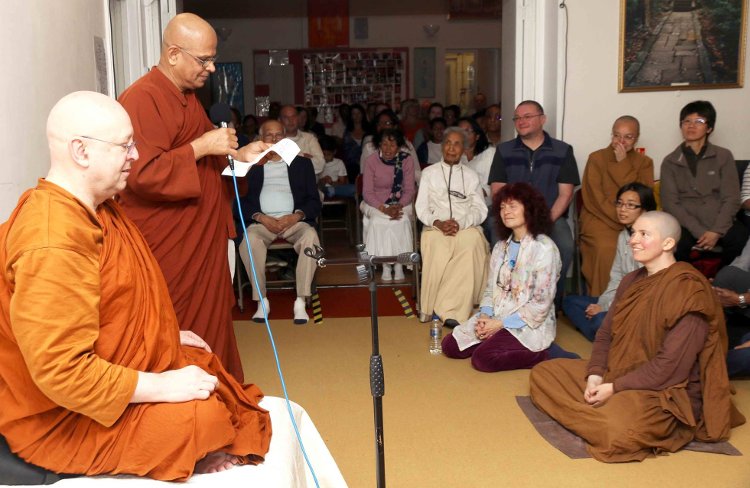

An Informal Interview with Ajahn Brahm (speaking with Ven Canda), on 19th January, 2018

VC: What basis is there for legal objections to the validity of bhikkhuni ordination?

AB: Basically, there are no legal objections. Its only politics; people getting used to the idea of female monastics.

VC: Many people cite the idea that the bhikkhuni lineage died out in the Theravada tradition and so the bhikkhuni ordinations now are not actually legal.

AB: That is not correct- the bhikkhunis really do not recognise Mahayana or Theravada- the lineage depends on the authenticity of the ordination procedure. That authenticity has been maintained from the Sri Lankan (tradition) to the Chinese, then back from the Chinese to the Sri Lankan. That is an authentic lineage. This has happened in the bhikkhu sangha too, many, many times. When it has died out in one place, like Sri Lanka, it has been imported say from Burma or from Thailand, so it is re-planted from strong roots in other countries, and that was foreseen I think, by the Buddha, so that it is very difficult for any of the sangha to die out. It may die out in one place, but then it can be replanted from another.

VC: OK, so that was due to the compassion and foresight of the Buddha.

AB: Incredible foresight, yes.

VC: So, what would you say to those who deny the validity of bhikkhuni ordination?

AB: It is valid until proven invalid; innocent until proven guilty. So, it is up to you to please prove that it is invalid. Now we do have many, many bhikkhunis throughout the world. They are here. Some countries used to say, ‘there are no gay people in our country,’ which was just total denial for the fake news- people just denying what was right in front of their faces. And so, (similarly), bhikkhunis are here. Now they are here, please go and prove that they are illegal. You can’t.

VC: Some people call you a ‘renegade monk’ because they think that you brought something back that is going against tradition. How do you see yourself in this- as a renegade or…?

AB: I was with Ajahn Chah when there was a monk sent from Bangkok to investigate him, because there were complaints about Ajahn Chah for being… (pauses) a renegade. What he was doing was keeping some of the Vinaya rules that were embarrassing people in Bangkok, that is: to not accept or receive any money. When anybody looks at the tradition they will find I’m a very traditional monk. Because I am very traditional and some of those monks have become very lax, they will dismiss you as a renegade. I do recall, even in the Franciscan tradition (and St Francis was also someone who went on alms), that during his lifetime he was invited by the Vatican, by the Pope, for a big feast. He took one look at the feast and went out on alms round to get some scraps from poor people and he gave those scraps to the Cardinal and to the Pope to show what a real mendicant should be like. St Francis was a ‘renegade.’ So, sometimes we do need those so-called renegades: The Martin Luther’s, the Rosa Parks’ (and Rosa Parks was a Buddhist when she passed away). These people were regarded as renegades because they saw some inequality- some terrible things, going against fundamental human rights and fairness- and they stood up. But they were strong enough to resist that (label) and became icons of freedom.

VC: Fantastic, great! Next question: how will the bhikkhuni sangha contribute to Buddhism as a whole?

AB: (Laughing): It has been well known through many studies that societies that have equity for women, especially in leadership positions- and of course one of those leadership positions is religious leaders- have far less incidence of domestic violence, sexual abuse, sexual slavery and prostitution. This is a link that has been found again and again in many social studies, so giving equity solves a huge number of social problems. But we cannot say, ‘OK, we will just have legislative equity,’ when we still haven’t had a female president of the United States; when google does not pay women doing the same amount of work the same pay- and that is part of the problem. And it’s an easy solution. When we give equity, we don’t look at a person as whether they are that race, religion or gender: if they can do the work, they get the job and they are paid for their work, not their gender.

VC: Do you think that female monastics will have a special role in enriching Buddhism in some way?

AB: Very much so, simply because we talk about compassion, fairness and equality- and, you know, the teachings of the Buddha are one thing and how people practice them is another thing. We must have that authenticity- obvious things to bring the teachings into line with what we do and how we work. One of the monks from here (a Dutch monk) had to ask his parents for permission to become a monk and his parents asked him, ‘Is there equity in the monastery where you wish to ordain? Do they treat women with the same respect as men- are there bhikkhunis?’ And he said ‘Yes!’ And that Ajahn Brahm is one of the leaders in bringing that equity back into Buddhism. And, at that, they said ‘Ah, OK, you may ordain.’

People want equity- and these are educated people coming from areas where we demand such equity. Remember we are not saying equality, but equity, which means equal access- you’ve got the same sort of skills and abilities, and you should be allowed to have the same opportunities.

VC: (In the context of Anukampa Bhikkhuni Project), could you please share what you feel is the hardest thing about establishing a monastery?

AB: Of course, the hardest thing is getting the people on board. Getting people first, and from those people, getting commitment. Even today, just doing a marriage blessing, (they need) to have that commitment towards one another and for that commitment to be there long enough to that cause and never give in. It’s the difference between bacon and eggs: the chicken is only involved but the pig is committed! So, the hardest thing starting off any monastery for bhikkhunis is to get that commitment. To determine you’re not going to stop, you’re going to keep on going, and then people realise it’s in everybody’s interest- we’re going to make this happen! You’re not going to just come in and then go away- bhikkhunis aren’t just going away- they’re here, they’re going to stay! Now is the time to support them.

VC: What is the most rewarding thing about establishing a monastery and seeing a good monastery run well?

AB: The most rewarding thing is that even though you are very tired (you give a lot, you really sacrifice), it’s called ‘renunciation’– of yourself. It’s called ‘letting go.’ Many people say those words: ‘renunciation’, ‘compassion’, ‘letting go,’ but most people just don’t have an idea what they mean. They want to practice for themselves, they want to be supported, they feel (pause)… entitled. But when you sacrifice, give up, let go, relinquish, physically you feel tired from time to time but then emotionally and spiritually you have this huge store of energy called ‘kamma.’ People talk about kamma, but you do that- you let go, sacrifice, give. When you do things like that then people see just how much you have sacrificed, Venerable Candavisuddhii; what I have sacrificed as well- giving up- and they find out that ‘Wow! That’s inspiring, we also want to help and give.’ Again, it’s not just writing out a cheque- that helps, obviously, to pay the bills and get things started- but more than that, people who give to the idea, give to the project, who, just like myself say: ‘We’re not going to stop until this happens.’ That is what leads people.

VC: Do you get a lot of joy seeing people benefit from the monastery?

AB: Oh absolutely. Even today at the wedding ceremony, some people came over from Germany and they were saying just how much they appreciated ‘Die Kuh, Die Weinte’ book (i.e. ‘The Cow That Cried’, otherwise known as ‘Opening the Door of Your Heart’). The groom wanted me to do the wedding to bring the spirituality of monastic life into their life together and there was just so much you could add to that occasion.

VC: We (Anukampa Bhikkhuni Project) only opened bookings for Ajahn Brahmali’s (first UK) retreat about 4 days ago, and I’m just amazed that we are already nearly full!

AB: Well, that’s quite slow- when I’m doing a retreat here (in Perth) its usually 5 or 6 minutes!

VC: And a lot of newcomers too, who’ve never sat meditation retreats before. They want to come because they feel Ajahn Brahmali can give them an introduction to what Buddhism really is- the whole context of the teachings.

AB: Also, because of who he is. You can teach like a scholar, you can know Pali better than Ajahn Brahmali and myself, but if you don’t understand where its coming from, you cannot tie that to the experience of the Eight-Fold Noble Path. If you have lived those teachings, not just studied them, it means that (the teaching) has far more power.

VC: That’s what we tried to convey; that the teachings are conveyed with so much joy and inspiration.

AB: Because you’re living it 🙂